Finding the ideal breakout distance is super important for any swimmer. Most of the time coaches just use their “coaching eye” to assess when a swimmer slows down in speed—but, did you know there’s actually a way to calculate what the ideal breakout distance should be for your swimmers? Plus, you can test how many dolphin kicks a swimmer should do prior to the breakout and/or transition to flutter kicking? Well, now’s your chance to figure out how!

Let’s dive in...

First off, Hi! I’m Abbie Fish. I’m Tritonwear’s new content creator. My passion is biomechanics and the hopes with my articles is to help you learn more about data analytics and stroke technique. The goal as we put more content out is to help you understand how to better use your Tritonwear system to improve your swimmer’s technique and track their progress over time.

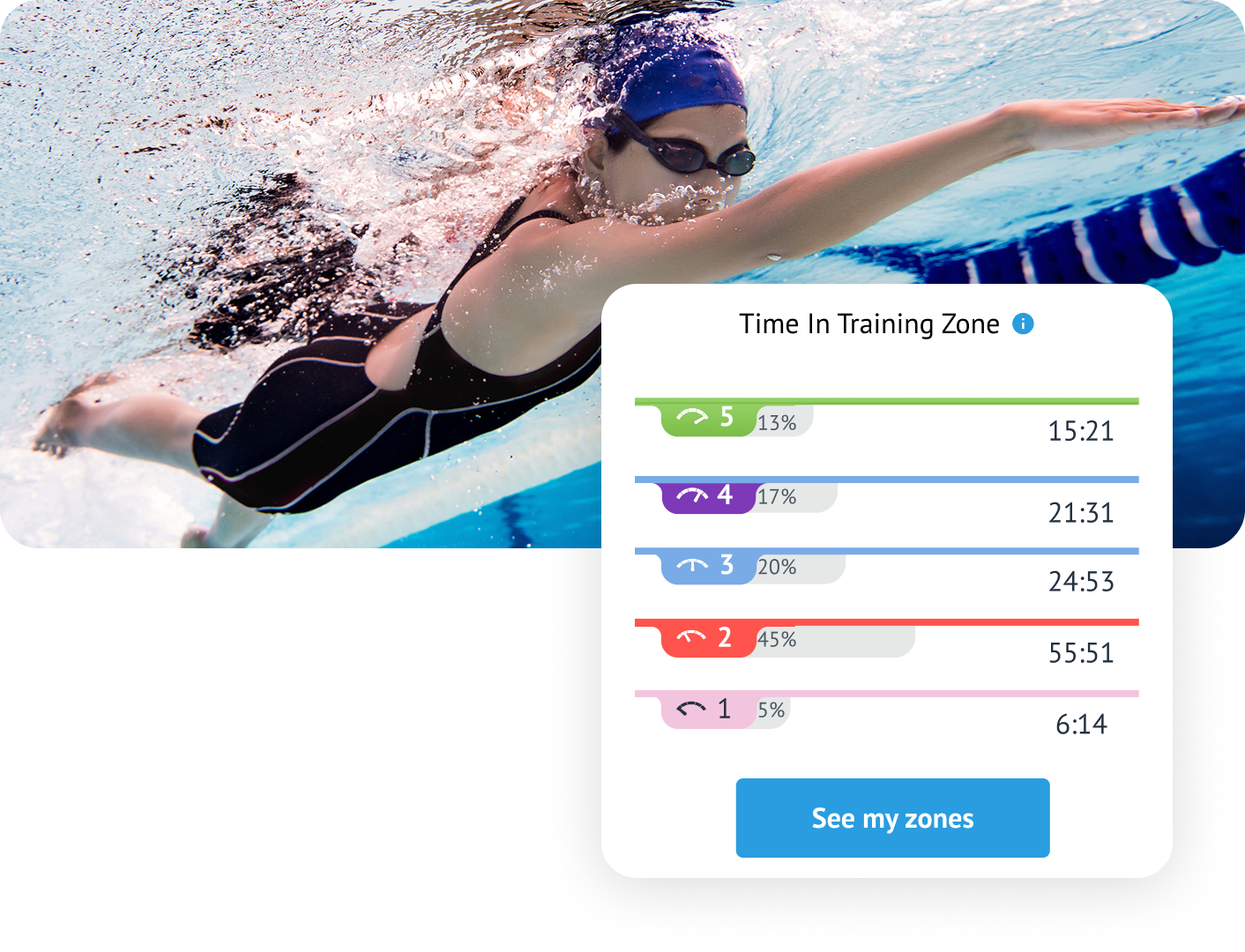

This summer, I’ve had the two awesome opportunities to do this exact test on hundreds of swimmers. My favorite part of the Tritonwear system is it’s motion analysis feature, where the testing for optimum breakout occurs.

But before we get into the nitty gritty of calculating the optimum breakout distance, let’s talk about why the breakout distance is important.

Well when you think about a breakout, you need to think about a few different aspects:

1.) It’s always off a start or a turn:

What this means is a swimmer is coming off their FASTEST or SECOND FASTEST point any swimming race (which is a start and turns, respectively) and the goal of that would be carry that high speed for as long as possible.

The reason a swimmer goes immediately into their streamline after a start or turn--is it is the most hydrodynamic position a swimmer can be in. The streamline has the lowest drag coefficient of any swimming stroke, which is why we do see that position happen immediately after a start or turn.

So once we get a swimmer in a streamline, we now need to figure out how long do they stay under for, which is why this optimum breakout distance test is so valuable.

2.) The 15m rule:

According to Fina, a swimmer cannot pass the 15m mark off any wall in a swimming race. This rule was created due to David Berkoff (and 4 others in the 1988 Olympic Final) that stayed under over 25m in the first 50 of their race. At first, the rule was only for 10m for Backstroke only. Then FINA changed it to 15m. Then eventually, FINA said every stroke had to follow the 15m mark rule.

So what does the 15m rule have to do with breakouts? Well, right now we are really seeing a trend in college swimming that the sport is becoming very heavily an underwater (hypoxic) sport. Most coaches and swimmers have figured out at this point, you are faster under the surface of the water (if you have a solid dolphin kick), than anything you can do above. So why break out sooner?

With the 15m mark rule though, a swimmer must make sure they surface before that line and once again, carry the highest average speed possible for the duration of time they stay under.

3.) The transition:

Water is more dense than air, right? Well to be exact, it’s about 800x more dense. So with breakouts, when a swimmer is about to break through the water—they are transitioning from a high drag environment to one with less drag.

The goal of this transition is to make sure that at the point of transition, your speed change would stay closer to zero. We obviously wouldn’t want a swimmer slowing down too much, because that means they could have stayed under longer-- AND-- we wouldn’t the opposite to happen either with a swimmer speeding up from staying under too long.

So understanding that during this transition from a high-resistance environment to environment with lower resistance is important when calculating the ideal breakout distance for your swimmers.

So how exactly do you calculate a swimmer’s breakout?

First off, you need to have the Tritonwear system with the motion analysis update. If you have that, then you’re good to go.

From there, grab one of your swimmers you’d like to work with on their break outs and ask them what their favorite race is to do. I normally like to have my swimmers pick their favorite stroke and one they are working on (if they are getting tested for the first time).

When you have both their favorite stroke/race and least favorite, ask them on average, how many dolphin kicks do they take off each wall during that race? This is the best way to gauge how many tests you’ll do with the swimmer. I would say the most common number I hear from swimmers is anywhere between 3-4 dolphin kicks. So with that number, I would do a test for 2 dolphin kicks, 3 dolphin kicks, 4 dolphin kicks, and 5 dolphin kicks or 4 tests total.

A good rule of thumb is to do one less dolphin kick than what they say and one additionally than their highest number too. This will help ensure the accuracy of the test as well.

After you have all that decided, you now need to get the unit on the swimmer and pull up the motion analysis software.

A quick tip on the motion analysis software is that anytime you are about to do ANY motion analysis— tell the swimmer right before they push off to double tap the unit twice with their pointer and middle finger. What this does is ensure they the acceleration profile is correctly synced with the point of push-off.

Also before running any tests, I always tell my swimmers they need to go as close to race speed as possible—because at the end of the day, we are not testing their training speed. The goal is to find how many dolphin kicks are ideal for them to do in a race (when they are fatiguing fast), so if a swimmer doesn’t go or try to go close to their race speed during these tests—the data will be thrown off and the tests won’t be accurate.

So once your swimmer understands the effort they must put for, have your swimmer wait for you to say "go" and from there--they need to double tap the unit and push off completing however many dolphin kicks they have for Test #1, as you walk alongside them and film.

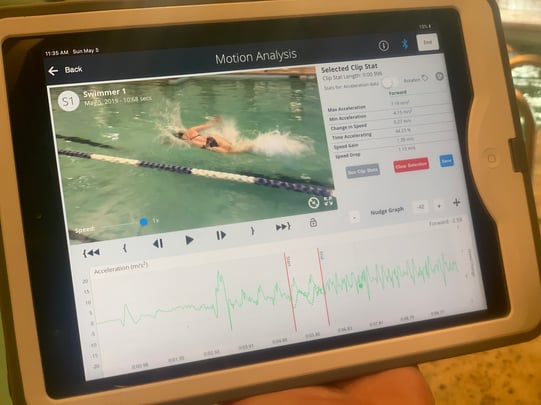

Once you’ve completed all the tests needed for your swimmer, now the calculating part comes in. Did you know with the motion analysis software you can add brackets anywhere to the acceleration graph and specifically look at the part between those brackets? That’s exactly what you are going to do here. See the picture below:

How do YOU go out adding these Brackets?

The brackets should be placed BEFORE last dolphin kick starts and AFTER the first completed, full stroke cycle.

More specifically, the first bracket should be prior to the “up-kick” of the final dolphin kick-- a swimmer’s body alignment should look similar to a streamline for where you place the first bracket. And the second bracket, should be at entry of the start of the second stroke. See the video below:

After you have the brackets placed in the correct positions, you will then look at the “selected clip stats” and find the metric: change in speed. Remember as we said above, we want the change in speed to be as close to zero as possible, because that means a swimmer went from a very similar speed underwater to about the same above water. It’s all starting to make sense now, huh... ;)

Here’s a quick chart of what the different changes in speed mean:

- Positive change in speed: means you accelerated after you broke through the surface. This isn’t good because it means you stayed under too long, and your dolphin kick are not strong enough to keep your speed high for that long of a distance.

- Negative change in speed: means you slowed down significantly after you broke through the surface. So you could have benefited with staying under longer, as you were much faster under the surface than above.

- Zero change in speed: means your transition was smooth and you held your break out long enough without decelerating or accelerating too much through the transition.

So when finish placing all your brackets and have all your changes in speed written down for the swimmer, the metrics will look similar to the ones below—it is now time to figure out which test is closest to that zero change in speed:

2 dolphin kicks: +1.15 m/s

3 dolphin kicks: +0.75 m/s

4 dolphin kicks: +0.2 m/s

5 dolphin kicks: -0.4 m/s

Using the data above, you would look for the point in which the swimmer’s data passes zero and/or is close to zero--which for the data above is between 4 and 5 dolphin kicks. The change in speed is CLOSEST to zero at 4 dolphin kicks, so your conclusion would be this swimmer’s optimum kick count is 4 dolphin kicks and they can continue to improve their dolphin kicks in practice, by playing with taking 4+ dolphin kicks off practice during their training sets.

We would love to hear how these test cases pan out for you guys and if you have any feedback for us during the process. The great part about Tritonwear is it takes away from any “guess-work” in your coaching and gets you the information you need, so you’re off to the races.

Until next time,

Abbie Fish

.png)